Below are three separate stories are about buried treasure near Inverloch that I have discovered and researched. It seems that there should be some sort of a connection between them but if so, I simply haven’t been able to find it. Maybe one day, you will make that connection!

Inverloch, 1954 and Donald Nicholson.

Near Inverloch, an elderly gentleman named Donald Nicholson spent 15 years digging for lost treasure amongst the sand dunes of Savages Hill. Donald claimed that in the late 1890’s his grandfather put a large amount of gold and jewels in a steel vault which he then buried near Inverloch. The grandfather, John Nicholson, was allegedly one of three men who were involved in shipping in the lucrative China trade route. China had been gripped by numerous wars and the men were involved in bringing food into the war torn region. Supposedly the food was paid for with gold and jewels looted from Chinese temples. The treasure was buried because the men did not trust banks and the group made his grandfather the trustee of the treasure. It was claimed that he buried it with the sanctions of his business partners. Supposedly Donald’s grandfather was the last member of the group to pass away.

The story is plausible. Certainly the economic depression of the 1890’s had wide repercussions on the Victorian community. Many individuals and businesses lost everything when the banks and businesses collapsed. Secreting and hiding your money was something that many Victorians were doing. And China was gripped by numerous wars during the period 1840 to 1890. The people of mainland China were suffering widespread hunger and death from malnutrition.

I have also found that there was a sailing vessel regularly doing the Australia-China run called the Hannah Nicholson. The boat was originally owned by a William Nicholson and at one point her master was A. Nicholson so it is entirely possible that Donald’s grandfather was involved in this business. What doesn’t add up is why his business partners (and their beneficiaries) weren’t making a large noise about the missing loot.

Donald and his wife Lillian were childless. During the 15 years they searched for his grandfather’s treasure they camped on the site. Donald claimed that the treasure had been left to him by his grandfather and that his father was the only person with the knowledge of it’s exact location. Supposedly he was to claim it on his 21st birthday but unfortunately he and his father had an argument when he was 20 and years later his father died before he could pass on it’s location.

In 1940 Donald contacted the Governor General asking for help and a group of 12 Army professionals including 4 engineers were expected to arrive. A plan was made to excavate the area, set charges and blow up the hill. At the last moment the plan was called off and Donald continued digging on his own.

As the years went on Donald became more and more strange. He became known as “The Hermit” from Inverloch. The value of the treasure lept from £10,000 to £200,000,000 and included Australia’s charter from England and a supposed formula from “Solomon’s Temple for the Nicholson Clan Dealing With Light and Energy”. Regardless, people were still treating the story as fact. There is a report that the Commonwealth Bank had set up a vault to take the treasure and that they had an armed guard ready to protect it.

In September of 1954 it was reported that Donald had a group of businessmen involved in the search for the treasure. Using a radioscope (an early version of a metal detector) they searched the area and found evidence of a large metal object less than 20 feet from the surface. Shortly after, on the 5th of October 1954 it was reported that Donald Nicholson was dead. Donald had taken ill and was taken to a Melbourne hospital where he died from a stroke. Right up till the end Donald still believed that the treasure was days from being found. When the object was dug up and it proved to be a long narrow black coal deposit. Over the following years Donald’s wife Lillian and two of her sisters continued to dig on the site fueling the story that the treasure was still to be found.

Memorial marker for James Price, His mother Lettice Price and father, William Price. Placed by their descendants. Photo courtesy of Billion Graves Project.

Inverloch, 1925 and James Price

Backtrack to 1925, when another elderly man named James Price passed away. James was a member the family credited with being the original white settlers of the area originally called Prices Corner, but now known as Dalyston. James’ mother and father arrived with a number of children to take up land in 1856. By 1925 James had a parcel of land on the Wonthaggi road at Inverloch while his brother farmed in the Archies Creek area. James never married but worked his farm, saved his money and even took up a block of land in the Northern Territory. Like Donald Nicholson, James didn’t trust the banks and he told his family that he had placed 160 gold sovereigns, some jewellery and important papers in a deed box. James suffered a stroke with paralysis and was unable to tell his relatives where he had placed the box. He did speak the one word,”dig”. His family searched, pulling apart much of his cottage and digging up the farm looking for the gold. It soon became well known around the area and many people searched for the elusive box. It was never found.

Tarwin Lower, 1877 and Martin Wiberg

And now we go back to 1877 and possibly the origin of all the buried treasure tales. This story begins with a large shipment of freshly minted gold sovereigns being shipped from Sydney to Sri Lanka. The coins were stamped with a very specific wreath design as requested by the purchaser. The shipment went from Sydney to Melbourne on a P & O ship called the SS Avoca before being transferred to the RMS China for the the trip to Galle. The gold coins had been placed in six strong boxes, banded and sealed then placed in larger boxes and surrounded by sawdust. This in turn was placed in the strongroom of the ship and the ship’s master had the only key. The contents of one of the six boxes disappeared during the voyage between Sydney and Melbourne but the theft wasn’t noticed until the shipment was unloaded at Galle (Sri Lanka). There were conflicting reports regarding on which ship the theft occurred and how the robbery was able to remain undetected for so long. In some reports it was stated that after the removal of the gold a quantity of bolts and iron or lead were placed in the inner box thus giving it a similar weight to the untampered boxes. This added to the fact that the boxes were moved in one lot all together meant that when the shipment was transferred from the SS Avoca to the RMS China it wasn’t obvious that one of the boxes was missing 5000 gold sovereigns.

The ship’s carpenter on the first part of the journey was a Norwegian who went by the name of Martin Wiberg (also spelled Weiberg or Wyberg). It was later shown that Wiberg was an alias and his true name was Olsen. During the voyage he was asked to repair the lock on the strongroom door and although he was watched, he was able to make an imprint of the key. It was also thought that the deck in which the strongroom was situated had only one entrance and this was guarded. After the robbery it was shown that there was a small hatch at the back of the orlop deck just large enough for a small man to fit through. The seals and bands on the gold boxes were cleverly cut and replaced so that the theft was not discovered until the shipment reached it’s final destination.

The delay in discovering the theft made the investigation difficult but eventually Wiberg was found to be a prime suspect. By this time Wiberg had left the employ of the shipping company and had married a woman named Rosina Brackley from Melbourne. In 1879, he and Rosina had a two year old daughter named Ethel Christina and Rosina was pregnant with their second child. Wiberg had taken up a selection of 120 acres at Tarwin near Inverloch and had built a small cottage on the land. When arrested, the officers searched the property and found two “plants” where Martin had secreted a quantity of the freshly minted gold sovereigns. One was a large carpenters plane casually left in a nearby hollow tree. The plane had been drilled and filled with 54 of the gold sovereigns and then the plug was replaced. The workmanship was so good it was virtually undetectable except for the excessive weight of the tool. 256 sovereigns were found in a drum of tallow and others were said to be hidden inside cakes of homemade soap.

At the selection at Tarwin the detectives found 310 of the 5000 missing coins. Later the officers were able to account for a further 1420 coins including ones that that Wiberg had sent to Melbourne for the purchase of a boat.

The detectives grilled Wiberg who confessed to the crime. It was obvious that he must have had an accomplice as it would have been very difficult to transport 5000 coins with a combined weight of 1500 kilograms without anyone noticing. Wiberg named the ship’s first officer, Robert Elliston. Elliston had resigned from P & O for health reasons and was living in England and so this delayed the investigation. Eventually it was proven that Elliston was innocent and after a long battle compensation was made for damages to his reputation. The accomplice was never found but one theory put about was that the accomplice brought a boat up alongside the Avoca while the Avoca was near Inverloch. The gold was transferred during the night and then taken through Andersons Inlet and up the Tarwin River.

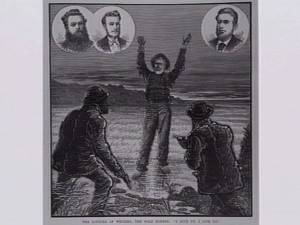

In an effort to locate the fortune, the police brokered a deal with Wiberg who was to take them to another of his “plants” near his selection on the Tarwin. Supposedly he had filled a kettle with 1700 or 1800 of the gold sovereigns and sunk it in the Tarwin river. Two detectives, Wiberg and a boatman named Tarwin Jack travelled up the river to a place that Wiberg had previously described. Using an improvised pole and hook the detectives started dragging the river with no success. Wiberg was not handcuffed and he helped the officers. His behaviour was exemplarly until the second day when an opportunity arose and he punched one of the detectives in the stomach and escaped.

Wiberg was on the run for about 5 months living rough in the bush around the Inverloch-Walkerville area. During this time he befriended a man named Pearce who took sovereigns to Melbourne and returned with goods for Wiberg. It was during this time that Wiberg sent a parcel containing sovereigns to the value of £1000 up to South Melbourne for the purchase of a boat. Pearce instead loaned £300 to a friend and the rest was found hidden in South Melbourne.

Wiberg was extremely cautious while on the run. He camped regularly in a cave near Eagles Nest, Inverloch being careful to cross the sand only when the tide was running in so that there were no footprints to be seen. He was an excellent swimmer and often swam across Anderson Inlet braving the freezing water and sharks. It was this that finally led to his capture. Using field glasses the detectives watched the inlet from Cape Patterson. In May of 1879 they spotted Wiberg swimming across. They recaptured him, he pleaded guilty and he received a sentence of five years.

Upon his release Wiberg and his brother purchased a small yacht called the Neva. In 1883 they sailed it to The Glennies, a group of Islands near Walkerville. Rosina was living in Walkerville (then called Limeburners) with their youngest child and working as a housekeeper for a local family. The story goes that Martin left his brother in the boat sheltering near the island and rowed a small skiff to Walkerville. The weather cut up very rough and he had been drinking. It was assumed that he had also visited one of his plants and collected up some of the gold. He tried to get Rosina and the child to come with him but Rosina refused. It was reported that many locals watched his small boat as he attempted to get back to the Neva. The waves were massive and the whitecaps were breaking over the bow of the skiff. A day or two later the skiff and some items including an oilskin coat belonging to Wiberg were found washed up on Yanakie Beach by a Mr. Mallar. It was generally thought that Wiberg had been drowned, possibly weighed down by gold sovereigns he may have had in his pockets.

The steamship Gazelle was in the vicinity and her master, Captain Leith went out to the islands and found Martin’s brother on the Neva. He was short of food so the Gazelle towed the Neva in to Walkerville. The brother refused to believe that Wiberg had drowned and many locals seemed to feel the same. It was reported that lights and fires were seen on the nearby islands and Captain Leith made another investigation of the islands. He reported that nothing was found. Eventually the Gazelle towed the Neva up to Melbourne and Rosina and her younger child were on board the Gazelle.

During this time there is no mention of the eldest child, Ethel Christina, who seems to have disappeared into thin air. Searching for Rosina’s death notice gave me a clue to Ethel Christina’s fate. I found that the Laycock family were neighbors of the Wibergs in Tarwin during 1879. The Laycock’s had a daughter born the same year as Ethel but named Matilda. Matilda grew up and married a man named Pescia. When I found a death notice for Rosina in 1940 one of her daughters is named as Mrs. Tilly Pescia. Obviously Rosina adopted out Ethel, probably during the time when Martin was in gaol.

In December of 1883 it was published that Wiberg had not drowned but had boarded the steamship Sorata and was on the way to London. Further rumours came about that Wiberg had settled in Sweden and owned a large hotel.

Just to add confusion to this incredible story it was reported 1n 1894 that a young man by the name of Radcliffe had discovered a skeleton while digging a drain at Waratah Bay. The skeleton was complete except for a small portion at the back of the skull. The general consensus of opinion was that it was Wiberg but of course this leads us to the question of who murdered him.

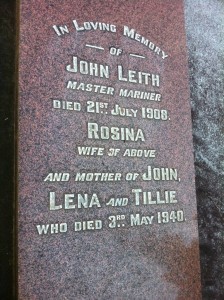

Headstone of John and Rosina Leith at Oakleigh Pioneer Cemetery.

Photo courtesy of Billion Graves Project

In 1884 Rosina married Captain John Leith, the master of the steamship Gazelle which had searched for Wiberg on the islands. In 1885 John and Rosina moved to Oakleigh and were the licensees of the Junction Hotel. Wiberg’s youngest daughter lived with them and over the coming years Rosina gave birth to two sons one of whom died as an infant. In 1908 John died and Rosina passed away in 1940.

No more of the gold was found until 1904 when a farmer near Inverloch found a stash of 75 gold sovereigns while chopping an old tree for firewood. In all, 1775 sovereigns were retrieved. This means that 3225 solid gold sovereigns with a minimum present day value of about 2 million dollars are still missing.

Another interesting twist to this story is that Wiberg’s original selection was sold to the Honorable Frances Longmore. Mr. Longmore and his sons searched the property for 15 years and never found a single sovereign. He in turn sold it to J and C. Widdis who sold to Peter Clement, who purchased it on behalf of his sisters Jeannie and Margaret Clement. This is the same property that centered around the mystery of “The Lady of the Swamp” the true story of the disappearance of Margaret Clement in 1953.

Relevant Buried Treasures Links

- Donald Nicholson, April 1954, Searching For Buried Treasure

- Donald Nicholson, Businessmen Continue to Search

- Donald Nicholson, Death

- Donald Nicholson, Economic Recession of the 1890's

- Donald Nicholson, Radiograph Locates Object

- Donald Nicholson, Radioscopes and Metal Detectors

- Donald Nicholson, The Hannah Nicholson

- http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/page/267639

- James Price Family History

- James Price is Dead

- James Price, Death Notice

- James Price, Electoral Roll 1924

- James Price, Land in N.T.

- James Price, Prices Corner

- James Price, Treasure hunters

- James Price, Treasure Hunters 2

- Wibegr, 1908 will of John Leith.

- Wiberg alias, Neva towed

- Wiberg arrested, October 1878

- Wiberg crewlist for The Avoca

- Wiberg implicates Elliston

- Wiberg re-arrested, May 1879

- Wiberg, 1893, skeleton found

- Wiberg, 1919 Rosina, electoral roll

- Wiberg, 1940, Rosina Leith death notice

- Wiberg, escape, Tarwin Jack and Laycock

- Wiberg, interview with Captain Leith

- Wiberg, Pearce took sovereigns to Melbourne

- Wiberg, Rosina and John Leith's grave

- Wiberg, skiff and oilskin found on beach

- Wiberg, sovereigns found 1904

- Wiberg, total of 1700 sovereigns found

- Wiberg, value of common gold sovereigns