Deep in the channel country of outback Queensland is a remote pastoral lease known as Arrabury Station. Situated about 100 kilometres north east of Innaminka and 180 kilometres south east of Birdsville, it is one of the most isolated places in Australia. Even more remote than Arrabury is an out-station on the pastoral lease by the name of Copracunda. It was here, during the Great Depression, that a boundary rider named William Henry Lissaman and his family lived in a rough bush hut. Comprising of just 2 rooms with a dirt floor, it truly was a primitive existence. It is quite possible that during the 16 years in residence at this tiny outpost the family never saw another white woman. The stores would have been dropped in by station employees and messages and letters would have been sent out the same way. The highlight to life would have been in 1931 when a journalist passed through stopping the night at Copracunda.

Prior to living at Arrabury, the Lissaman’s had worked at cattle stations in the Channel Country where William and his wife Rubie took on employment as a married couple. Rubie would cook and look after the children while William rode a stock horse and did rough outback work. Rubie came from a good Sydney family, she was a well educated and softly spoken woman who had had a falling out with her parents many years earlier. Small of stature and looking much older than her 44 years, Rubie was well loved on the stations where she worked and most of the menfolk referred to her as “Mother”. William was quite the opposite. Apparently hailing from San Francisco, William tended to bully and bluff his way through the outback.

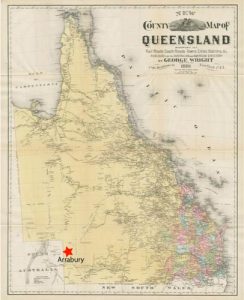

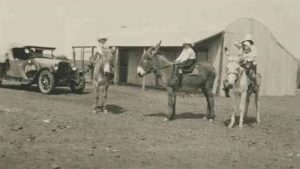

Four Children on Donkeys. Arrabury Station Approximately 1925. Photo Courtesy of the State Library of South Australia

The Lissaman’s had 4 children, two girls and two boys. By the time this story occurred their eldest daughter was married and living on another property but the younger ones feature in the tragedy. Gladys was aged 13 and gave evidence at length before the judge during the trial, while young Henry at 12 years old and Keith at 9 were also interviewed. Also featuring in this sad tale was another station-hand known as Toby Stephens.

William was known for his sexual appetite. He is referred to at times as a sexual maniac and would use his position to force liaisons and probably rapes of the local indigenous population. At times he even brought them into the hut and bed he shared with his wife and children. It also become known that he used his own children for sexual gratification. The isolation of the family and the severe financial situation made it easy for William to use violence and threats to achieve his aims. And William was rather handy with his fists and a stockwhip. The young children became used to regular beatings from their father, often with little or no reason. When asked by the judge, none of the children claimed to have any love for the man.

This story is not just about the Lissamans. It is also about how isolated and vulnerable outback life was. After the murder, Mounted Constable John Finn travelled for 48 hours non stop to reach the scene. Constable Finn was a South Australian police officer at Innamincka but was made a special constable of the Queensland police in this outback territory. The Queensland constable who came from Noccundra had an even harder journey to make. As the Perth daily newspaper put it “He had to leave his car on the banks of the Cooper River and cross the flooded stream and two side channels by boat while swimming his horses. He walked and carried his swag about eight miles between the two channels and eventually he reached Arrabury station five hours after Constable Finn.”

In this isolated existence the children were supposed to do their schooling by correspondence but William refused to allow this to happen. Rubie would wait until William was away tending the stock then teach them herself. When he found out, he broke their slates and destroyed the few books that the family owned. The children became used to their father’s temper and would put their heads down and try to stay out of his way. In the days prior to the murder William made threats of shooting the family and of murdering the station-hand named Toby. He also talked of poisoning his wife and maiming the children and no one doubted that he would do it. But he must have realised that his violence was out of control because he also spoke of taking the children into town and putting them in the protection of the police. Rubie stated that she was going wherever her children went. I think Rubie realised that with the children gone her chances of survival were very low.

Meek little Rubie had befriended the station hand named Toby and her husband William became insanely jealous. As William’s behaviour became more and more erratic, Rubie, Toby and another boundary rider named Dick Griffin planned the family’s escape. On July 17 they would wait for William to do his rounds, then Griffin would come for them with his horse and dray. But the plan failed when William insisted on taking young Henry with him. Just before they left, he talked of maiming Henry with an axe and then he went to the shed and attached one to the side of his saddle. Rubie ran for Toby who confronted William and then spent the day tailing the father and son.

Toby was due on another out-station but decided to sit tight in an effort to protect Rubie and the children. That night William made known that he was going to shoot them all in the morning. Then in odd behaviour for him, he kissed each of them goodnight. Rubie and the children huddled together, unable to sleep as they waited for daybreak. As the morning sun rose Toby came across and had breakfast with the family and then took the two young boys back to his hut. Young Gladys was cleaning the bedroom when a shot rang out. Her mother entered the room placed the shotgun in the corner and with a slight smile on her lips said “I have shot him”. That was the official story. There are some who believe that mother took the blame and that one of the others may have pulled the trigger.

Managers office at Arrabury Station, 2016. Photo by Annie O’Riley. It was from this building that a telegraph was sent to the police notifying them of the murder.

Two days later, after his long and gruelling journey, Constable Finn found the body of William Henry Lissaman lying face down in the dirt, his death caused by a shotgun blast to his back. Toby Stephens had placed a groundsheet over the body then driven to the main station to raise the alarm. The man was dead but the nightmare was far from over. Constable Finn buried the body to preserve it while waiting for the coroner to arrive. During this time he arrested Rubie and then they started the journey to Quilpy. The three children travelled with them and during the journey had their first glimpse of civilisation.

After arriving in Quilpy it became apparent that there was no suitable prison cell for a female so the family and the policemen travelled to Brisbane where Rubie was incarcerated at the notorious Boggo Road Gaol. Showing how miserable Rubie’s life was, she commented that the gaol was like a lovely holiday. The children were sent on to a boarding house at Charleville and the local police officers and the community bought them little treats such as chocolates and sweets.

On September 6, 1935 the trial of Rubie Irene Lissaman was held at Charleville. A jury was selected and Rubie pleaded not guilty by self defence. Despite William being unarmed and having been shot in the back, the jury took only five minutes to find Rubie not guilty. The courtroom erupted in a round of applause and the judge gave the following statement. “Mrs. Lissaman, you are discharged. I sincerely hope that your future life will be happier than your past life and that you and your children will have some kindness shown to you.”

Relevant The Arrabury Station Incident Links

- Arrabury Station, About

- Beaten with a Stockwhip

- Birth Certificate – Rubie

- Boggo Road Gaol, About

- Brought Other Women Home

- Children Give Evidence

- Children See Civilisation

- Death Certificate, William Henry Lissaman

- Dick Griffin and Plans to Leave

- Difficult Journey for Police

- Electoral Roll, 1913, William Henry Lissaman

- Electoral Roll, 1930, William and Rubie

- Electoral Roll, William and Rubie, Arrabury Station, 1919

- Gaol Like a Lovely Holiday

- Incest

- Put the Children in Police Custody

- Rubie Irene Davies Lissaman, About

- Verdict, Not Guilty

- William Henry Lissaman Family Tree

- Woman Charged