While researching the article “A Lucky Black Cat” I came upon some other unusual articles. The first was a bit disturbing. It was published on Saturday December 9, 1916, in the Examiner (Launceston). Spelling and punctuation as per the original articles.

“ATTEMPTED POISONING

MELBOURNE, Tuesday

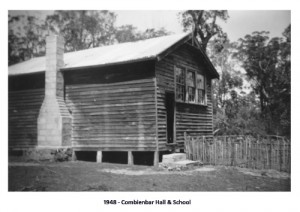

At the Sale Supreme Court today, Leslie Thompson, aged 14, pleaded guilty to a charge of having administered poison in a manner likely to endanger life, at Combienbar, on September 20. The facts were that Thompson was living with a family at Combienbar, with whom John Patrick Ward, the schoolmaster, a single man, was boarding. Ward was also postmaster. A sum on money £1- belonging to the state school, was missed and Thompson was suspected of the theft. Knowing that Ward suspected him, Thompson set about trying to remove Ward. He obtained a tin of strychnine and put some in the milk and in the teapot which was used by the family with whom Ward was boarding. Ward, instead of drinking his tea, went outside and threw it away. The milk was thought to be bitter and was thrown out. Ward was in the habit of taking breakfast later than the family, and porridge was set aside for him on the stove. Into this Thompson stirred some strychnine. Ward gave a spoonful to one of the children, who said it ‘tasted nasty’ and spat it out. Ward then tasted it and noticed that it was unpleasant. The porridge was thrown out to some animals and a dog and a pig, which ate some of it, died. Ward had a habit of sucking his pen and on this Thompson smeared strychnine. Ward put the pen into his mouth and only saved his life, by causing himself to vomit, by placing his fingers down his throat.

Mr. Justice Hodges said that it was a most diabolical attempt to take life. The schoolmaster was the one Thompson wished to hit, but he did not care how many suffered or how many lives were endanged. If Thompson were a bit older, there was not the slightest doubt that he would have been hanged. Thompson was sentenced to three years imprisonment with hard labour.”

In this second article, the writer manages to convey the isolation and beauty of East Gippsland with a little touch of humour. Published in The Argus, Monday, 21st of December, 1931.

Gippsland Gold, The Combienbar Valley

By C.R.C. Pearce.

Twenty years ago, I visited the Combienbar, when writing a series of articles to illustrate the trials of pioneers of East Gippsland through lack of good roads, and stayed a night at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Stagg, whose son, Mr. Noel Stagg, and Mr. Conrad Olsen recently discovered a rich gold reef in Errinundra Creek, four miles north of Combienbarr. The valley, set between high, rugged, heavily timbered hills was then a most isolated place. The only means of communication with the outside world was by a bridle track 14 miles long over the range to Club Terrace. In the hills, prospectors were then searching for gold, and the Golden Creek Mine was being worked. Everybody was confident that a payable reef would be found, but it was realised, even in those days of comparatively low mining costs, that the reef or lode would have to be fairly rich in gold contents to yield remunerative results, because the district was so far removed from a good road or a railway. But a great change in communication has come over the scene since then.

When with Councillor John Johnston who was, indeed, ‘guide, philosopher, and friend’, I left Orbost with buggy and pair one sunny morning in July, 1911. Our equipment consisted of two saddles and bridles, an axe, and a rope, and two bags of chaff in case of need of food for the horses. For food for ourselves we had to rely upon three hotels in the huge remote district we were to traverse and upon the hospitality of settlers. The Princes Highway was then only a vision. If I remember rightly, there was but one motor-car in Orbost, and the railway line from Bairnsdale had been surveyed and some clearing done in the forest.

Marlo, at the mouth of the Snowy River near Orbost, was almost the exclusive fishing resort of a few Melbourne doctors, who in fine weather had succeeded, to the wonderment of the settlers, in reaching the little maize port by motor-car, being aided at times by bullock and horse teams. I have since driven by car along the Princes Highway to Mallacoota and have marvelled at the splendid road and the comfortable and even luxurious provision made to travelers along the route. My journey with Councillor Johnstone, despite the occasional hardships, including a nights unrest, during a sharp frost, on a sheet of bark for a mattress, will always be remembered as a delightful experience.

The Pig as a Pet.

When Councillor Johnstone and I reached Cabbage Tree Creek on the afternoon of the first day of our journey, (which occupied a fortnight), there was no hotel to lunch at, but Mrs. Tarbuck was our hostess. Her husband was dead, so she worked the farm by herself, with the aid of a neighbour’s boy. A few weeks before our visit, Mrs. Tarbuck had bought 43 heifers at Warragul, and with the help of the boy had trucked them to the station, derailed them at Bairnsdale and driven them along the 70 miles of forest road and track to Cabbage Tree Creek.

We had turkey for dinner, a special feast in honour of Councillor Johnstone, who many years before had guided Mr. and Mrs. Tarbuck through the forest to their lonely selection on the creek. We had no more turkey on that trip. Sometimes we had bacon for breakfast, bacon for lunch and bacon for dinner. Often when we had jogged on for hours, with not a sign of a house or man or beast or even a post and rail, Councillor Johnstone would break the silence, ‘I think I can smell that turkey,’ and in a few minutes we would come to a clearing in the timber. If we did not have turkey we had a hospitable welcome at the fireside, and one by one, shy children would appear from behind mother’s skirts. Instead of a dog or a pet lamb, a cherubic pet pig, plump and pink with roguish eyes and curly tail, would follow at the children’s heels.

Well brought up pigs are not unclean, but one has to go to East Gippsland to appreciate his many virtues. I shall never forget my impression of a mob of 500 pigs on the way from Orbost to Cunningham. They looked both jolly and pathetic as they reached the top of a hill and all lay down in the shade for a rest, and snorting and grunting in complaint of the trying heat on this bright winter afternoon. Now they no longer toddle to market by easy stages of six or seven miles behind carts from which maize is sprinkled to lure them on the weary way and with pleasant camping places by running streams with muddy banks and roots to grub. Now they are rushed and bumped to market in motor- trucks from which they get fleeting glimpses of rivers, roads and maize crops; and so they are robbed in the modern rush of a few more days of blissful existence.

An Isolated Gully.

Club Terrace, which is about 40 miles fom Orbost, was once a mining camp, but when I visited it, tall scrub had covered the clearing where the canvas tents of the alluvial diggers had nestled and the hotel had been destroyed by fire. The small settlement included a store and a schoolhouse. From Club Terrace to Combienbar there is now a good road, but when I was there the road ended at Club Terrace. The diggers must have had rough journey from Orbost to Club Terrace, for even in 1911 we had to cut saplings with the axe and tie them to the axel of the buggy to act as brakes as we descended a track which was mostly a water channel down a steep hill. But prospectors for gold in East Gippsland from the sixties have always had to put up with great hardships.

As we were riding over the range to Combienbar the tinkling of a hidden stream called me from the saddle, and as I left the track Johnston said, ‘Don’t lose yourself.’ In the same country, a home missioner tethered his horse while he made his way first through tall timber and then through a thick jungle of shrubs to the water. The remains of the horse, still tied to the tree were found months later. A settler was lost a year or two later, but he was found and nursed back to life. in his wild wanderings he had stumbled upon a skeleton believed to be that of the lost missioner. Above the treetops on a neighbouring range rose a column of blue smoke. It seemed near by, yet it was one days journey away by hard riding.

Into the fertile Combienbar Valley, when Johnston and I reached it, no vehicle had entered. Supplies came over from Club Terrace on packhorses, and pigs and cattle walked out to market. Next to man and woman and horses and cattle, the pigs were the pioneers of East Gippsland.

The greatest possession in the valley was Mrs. Stagg’s stove. The appetising smell of Mrs. Stagg’s bread in the baking penetrated to the prospectors in the distant hills. When Noel Stagg was a small boy, he heard many a prospector say, as he jumped off his horse, ‘It was baking day yesterday, Mrs. Stagg. I’m sure it was. We could sniff it up in the hills, and it didn’t seem like damper.’ It was a hard worked stove, hauled over the range after many hours of toil, with the constant fear that by some mishap it should meet the fate of a plough that had toppled down a slope.

So secluded was the valley except to the few prospectors and settlers that the children regarded the sun and moon as their own possessions. A little girl was drawing a pail of water out of the creek, as I was watching the rising sun giving light and shade in his own inimitable way to hill and valley. She followed my eyes and said ‘We all like our sunrise.’ Soon afterwards she added ‘And you ought to see our moon.’ But long before the moon rose, I saw pigs at a call, solemly but cleverly walk a log which crossed a creek and eat for supper such pumpkins and melons as city folk admire at the Show. And nearby grew large violets and mignonette.

There is undoubtedly a great stretch of auriferous country from Combienbar to Bendoc, but the map gives no idea of the difficulties of transport when the main roads are left behind. Only experienced bushmen can penetrate this wilderness without losing their way. East Gippsland has always kept a close grip of it’s secrets, but there is no reason why prospectors, well guided and well equipped, should not unlock more of it’s hidden treasure.

Published on the 25th of February in 1935, this last article illustrates the remarkable environment of the remote East Gippsland area.

“Four Feet of Water Races Over Flat.

A Horse Drowned

With little warning, at about 2:30 p.m., last Thursday, a deluge of rain occurred in the Combienbar Valley. It was literally a cloud burst, and the river rolled down with a front of four feet sweeping everything before it.

Messrs. Stagg, Farmer, Clay and others were the main sufferers, but luckily the majority of the green beans had been marketed.

During the rush of water, one of Mr. Liney’s horses was washed downstream and had it’s side pierced by a snag and drowned. Several others escaped by swimming to safety.

The storm swung towards Gelantipy and caused a flood in the Snowy River on Friday last.”